What Scott Adams' Dilbert Got Right About Power at Work

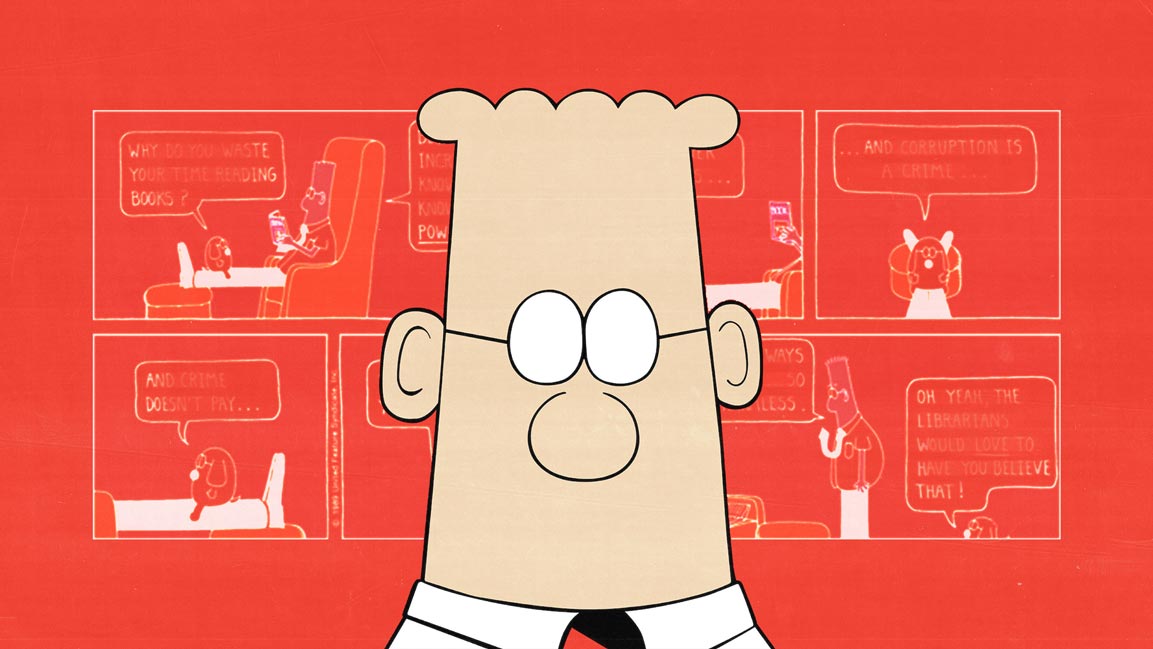

American cartoonist Scott Adams turned everyday office dysfunction into a lasting commentary on how organizations really operate.

Topics

News

- Meta Shifts Resources From Metaverse Toward AI, Wearables

- India Tells Quick Commerce Apps to Drop 10 Minute Delivery Pitch

- What Scott Adams' Dilbert Got Right About Power at Work

- Apple Turns to Google to Power the Next Phase of AI

- Nvidia, Eli Lilly to Invest $1 Billion in AI Lab to Speed Up Drug Discovery

- Anthropic Tests ‘Cowork,’ an AI Tool That Can Act on Files and Folders

Scott Adams, the American cartoonist whose Dilbert comic strip became a global shorthand for the absurdities and frustrations of corporate life, died on Tuesday, 13 January, at the age of 68. His first ex-wife, Shelly Miles, announced his passing during a livestream, saying Adams had been battling metastatic prostate cancer.

Adams’s Dilbert debuted in 1989 and grew into one of the most widely syndicated comic strips in the world, appearing in thousands of newspapers across more than 70 countries at its peak.

The strip’s hangdog protagonist, a bespectacled engineer in a white shirt and perpetually crooked red tie, pulled back the curtain on cubicle culture and managerial incompetence with a blend of deadpan humor and existential resignation that resonated with white-collar workers globally.

The cartoon introduced memorable characters whose names and traits became part of corporate folklore. Among them was Asok, an Indian intern, described in Dilbert lore as a brilliant graduate from the Indian Institute of Technology, whose idealism, naivete, and relentless optimism highlighted the often ridiculous demands of corporate hierarchies.

Created by Adams in 1996, Asok’s presence underscored the strip’s wider commentary on talent, bureaucracy, and global workplace culture.

Adams’s path to cultural prominence was unorthodox. After earning a BA in economics and later an MBA, he worked in corporate roles before pursuing cartooning full-time in the mid-1990s.

Dilbert soared in popularity during the tech boom, capturing the zeitgeist of office life with sharp satire and a tone that was equal parts caustic and relatable.

The strip’s success spawned books, merchandise, and even television adaptations, and Adams himself became a bestselling author with titles like The Dilbert Principle that further explored and satirized workplace absurdity.

At the height of its influence, Dilbert became more than a comic strip; it was shorthand for office dysfunction.

Executives and employees alike recognized themselves and their colleagues in its panels, a testament to Adams’s knack for distilling workplace culture into iconic, biting vignettes.

What Dilbert got right, long before management theory caught up, was that power at work rarely follows competence. Adams’s cartoons consistently showed authority flowing upward not to the most capable, but to those best insulated from consequences.

Managers were not villains so much as products of incentive systems that rewarded visibility over judgment, process over outcomes, and compliance over intelligence.

The pointy-haired boss became enduring precisely because he was familiar. He wielded authority without understanding, spoke in buzzwords, and made decisions detached from frontline reality.

In doing so, Dilbert captured a structural truth about organizations: hierarchy often amplifies ignorance while muting expertise. Employees like Dilbert and Asok were competent, ethical, and motivated, yet powerless to influence outcomes that directly affected their work.

The strip also anticipated a more globalized workplace. Through characters like Asok, Adams highlighted how talent circulates internationally while power remains localized and opaque.

The tension between globally mobile skill and rigid corporate hierarchy remains a defining feature of modern organizations, particularly in technology-driven industries.

In reducing complex organizational failures to four-panel vignettes, Dilbert did what many leadership books struggled to do. It made visible how power actually operates day to day, not as charts or strategy, but as lived experience shaped by incentives, hierarchy, and human weakness.

Yet, Adams’s career was also marked by controversy. In 2023, after making racially charged comments on his podcast that were widely condemned, hundreds of newspapers dropped Dilbert from syndication, and his publisher severed ties.

Adams defended his remarks as hyperbole, even as critics argued his commentary undermined the very audiences that had embraced his earlier work.

In the years that followed, Adams continued to publish through subscription platforms and maintain an outspoken online presence on social media and his show Real Coffee With Scott Adams.

He publicly shared updates on his health after being diagnosed with aggressive prostate cancer in 2025, which had spread to his bones. His ex-wife read a final message from him in the livestream announcing his death.

US President Donald Trump, who Adams had admired and praised in public, offered condolences on social media, calling him a “Great Influencer” and acknowledging his battle with illness.

Adams’s legacy is complex and conflicted. On one hand, he reshaped how millions think about the modern workplace, turning cubicle ennui and corporate cliché into an art form.

On the other, his later years were overshadowed by controversies that led to professional setbacks and spirited public debate about the boundaries of satire and personal commentary.

Among the enduring legacies of Dilbert are characters like Asok and the pointy-haired boss, whose names have entered corporate parlance and whose antics reflect, often hilariously, sometimes uncomfortably, the contradictions of contemporary office culture.