Why AI Is Not the Jobs Villain Yet

Companies are leaning on AI as a convenient explanation for layoffs, even as weaker demand, past overhiring and cyclical slowdowns account for most job losses, shows Oxford Economics research

News

- Sebi Taps AI to Purge 120,000 Misleading Finfluencer Posts

- Enterprise AI Scales Fast, but Structural Change Lags, Study Finds

- Airbus Grows Bengaluru GCC Footprint with New Long-Term Lease

- India Inc Issues Advisories as Middle East Tensions Escalate

- Inside OpenAI’s Pentagon Deal and the Three Red Lines on Military AI

- OpenAI Partners with Amazon and Microsoft

Companies are increasingly blaming artificial intelligence for layoffs, but the evidence that AI is driving a broad jobs shakeup remains thin, with job losses still largely explained by cyclical slowdowns and the unwinding of past overhiring, according to an Oxford Economics research briefing.

The report argued that while there are real pockets of disruption in occupations and sectors exposed to automation, firms do not yet appear to be replacing workers with AI at scale. As a result, Oxford Economics said it doubts unemployment rates will be pushed materially higher by AI in the next few years.

The note takes aim at a popular narrative that generative AI has already hollowed out entry level work, pointing in particular to the recent rise in graduate unemployment in the US and other advanced economies.

Graduate Unemployment Looks Cyclical

Since ChatGPT’s public launch in November 2022, the US recent graduate unemployment rate rose from about 3.9% to a peak of 5.5% in March 2025, a move that has been widely cited as evidence that firms are using AI to do tasks once assigned to junior staff, especially in professional and technical services.

Oxford Economics said that conclusion relies too heavily on correlation. The report noted that the recent graduate unemployment rate later fell after March 2025, which is hard to square with the idea of a steadily intensifying AI shock.

It also pointed out that the increase from 3.9% in November 2022 to about 4.9% by August 2025 does not look extreme, and broadly tracks unemployment trends among other graduates, with any apparent shift in the relationship between new graduates and other graduates seeming to predate the widespread launch of generative AI.

History, the authors argued, makes a cyclical explanation more plausible. In prior US downturns, graduate unemployment typically rises more sharply than overall unemployment, and the latest move looks consistent with that pattern, the report said, citing its historical comparison chart.

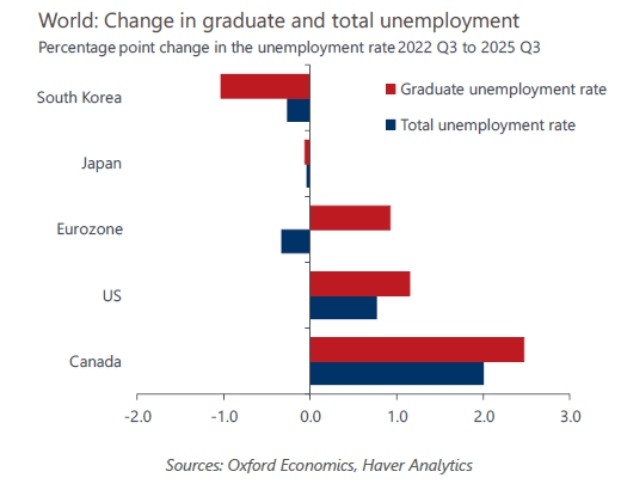

Cross country comparisons point in the same direction. In a bar chart, Oxford Economics showed that the biggest increases in graduate unemployment over 2022 Q3 to 2025 Q3 line up with economies where overall unemployment also rose the most, such as Canada and the US, while places with steadier labor markets such as Japan and South Korea saw much smaller changes.

The pattern, it said, looks like normal labor market softening, not a clean AI driven structural break.

Even where AI is likely influencing employment decisions, the report argued the mechanism may be subtler than direct substitution. Research cited from the Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis finds larger increases in unemployment in sectors that show higher reported AI adoption and where tasks appear quicker to complete with AI.

But that does not necessarily mean workers are being replaced by algorithms. Firms experimenting with AI may be redirecting budgets toward technology and away from wages, squeezing headcount without AI fully taking over the work.

Oxford Economics also leaned on a basic sanity check. If AI were already replacing labor at scale, productivity growth should be accelerating as output is produced with fewer workers. Instead, productivity has been “weak and volatile” across major advanced economies since the release of generative AI, according to the report’s chart comparing the US, Japan, the Eurozone and the UK.

The briefing said the post pandemic US productivity burst likely reflected firms using hoarded labor more efficiently, and the more recent slowdown looks cyclical rather than AI driven.

AI Makes a Convincing Scapegoat

Layoff attribution data tell a similar story. Challenger, Gray and Christmas data showed AI related job losses rising, with almost 55,000 US job cuts attributed to AI in the first 11 months of 2025, more than 75% of all AI related job losses reported since the category began appearing in 2023.

Yet those cuts amounted to only about 4.5% of total reported job losses in the Challenger data, the report said. Layoffs attributed to market and economic conditions were more than four times larger at 245,000.

The authors also note that in a typical month, roughly 1.5 million to 1.8 million US workers lose jobs for all reasons, underscoring how small AI attribution remains in the flow of labor churn.

The report is skeptical even of the AI attributed numbers, arguing they are more likely overstated than understated because “AI” can be a more investor friendly explanation than weak demand or managerial mistakes. Dressing layoffs up as modernization can be easier than admitting overhiring.

Another under-discussed driver of graduate unemployment may be simple supply. Oxford Economics pointed to a rising share of young people with university education, from 32% to 35% among US 22 to 27 year-olds since 2019, and a sharper rise in the Eurozone, where the share of 25 to 29 year-olds with university education climbed from 39% in 2019 to 45% by 2024. With larger cohorts entering as vacancies cool, graduate unemployment becomes more sensitive to cyclical hiring slowdowns even without a distinct AI shock, the report said.

Oxford Economics does not dismiss the risk of a sharper AI labor shock later. It reiterated its longer term view that AI could drive significant displacement in some sectors over time and said disruption could rise quickly if the technology improves and adoption broadens. But it framed that as a risk, not a baseline.

The briefing also highlighted reasons the transition may prove slower and messier than the hype suggests. It cited the example of Klarna, whose chief executive said the company planned to partially roll back 700 job cuts linked to AI after customer service quality suffered.

Separately, the report pointed to US survey evidence suggesting AI adoption at large firms has leveled off or even declined, particularly notable because big companies are where displacement would be most likely.

Part of the problem is that task-level time savings do not automatically aggregate into firmwide or economywide gains. The report said AI can improve process efficiency, but meaningful productivity gains often require reorganizing multistage production to remove bottlenecks, a process that historically takes years.

It also warned that AI can create negative spillovers that blunt headline efficiency, using hiring as an example. If AI helps jobseekers apply to more roles and helps firms screen faster, the result may simply be more mismatched applications rather than a cleaner labor market.

The bottom line, Oxford Economics said, is that AI adoption is real and job losses exist in some slices of the economy, but the macro impact remains limited for now. The firm said it does not see enough evidence to make a major upward adjustment to near term productivity forecasts or unemployment projections on the basis of AI alone.