The Leadership Test No One Wants: Delivering Bad News Well

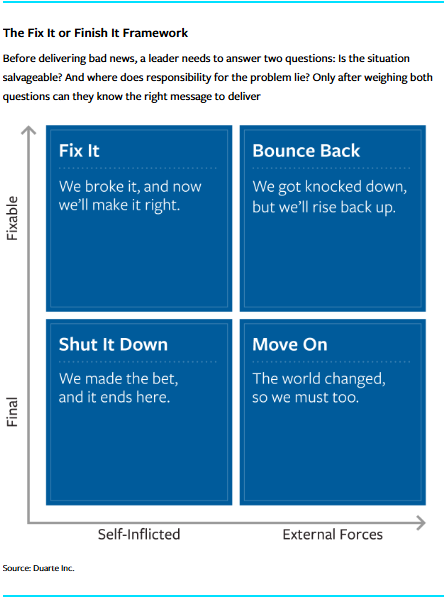

Good communication in tough times requires grappling with where responsibility for the problem lies and whether the situation is salvageable.

Topics

News

- Adani Power Sets Up Nuclear Subsidiary

- Musk Unveils xAI Overhaul, Lunar AI Ambitions

- Former GitHub CEO Dohmke Raises $60 Million to Build AI Code Infrastructure

- Leadership Shakeup Deepens at xAI as Two Co Founders Exit

- India Slashes Social Media Takedown Window to Three Hours

- Cisco Moves to Relieve AI Data Center Gridlock With New Chip

EVERY LEADER EVENTUALLY faces the moment they dread most: standing before their people to deliver bad news. It’s the test no one asks for, yet it arrives for everyone who leads.

When delivered poorly, bad news can drain trust and morale. It can sap the energy of the very people you need most to push through. When handled well, it can preserve dignity, free resources, and create momentum. The challenge isn’t whether you’ll face it but how you’ll respond.

Not all bad news is equal. Some situations are fixable. These require resilience and collective problem-solving. Others are final. No amount of effort will change the outcome, so the leadership job is to create closure and redirect assets to higher-value work.

When delivering bad news, its origin story matters. Sometimes the problem is self-inflicted, through decisions, execution gaps, or strategy errors inside the organization. Other times the force is external, through market shifts, supply shocks, or technology waves.

Together, these two dimensions create four kinds of leadership moments. Let’s take a look at them.

Shape the Message You Want to Deliver

It might seem obvious, but it’s worth saying: Before delivering bad news, leaders need to know what they’re going to say.

If you can name which moment you are in, you can communicate with clarity.

If you can name which moment you are in, you can communicate with clarity — helping people either build resilience if the problem is repairable or find closure if it’s final. In my experience in the communication industry, I’ve seen leaders barrel forward with emails or staff meetings without being clear about the message they want to convey. Good communication demands grappling with what happened and what’s next.

Below is a simple framework I recommend to my clients to help them think through where they are.

Each quadrant in the framework presents a different message to go along with the bad news: Either we’ll fix it, we’ll shut it down, we’ll bounce back, or we’ll move on. Each message demands a different way for leaders to show up. Here are examples of each message in action.

The ‘Fix It’ Message

This is the message to use when your own organization created the situation that has gone south, but the situation can be solved. It’s tempting to hide when you suffer a self-inflicted wound, but your credibility starts with owning the problem.

I’ve experienced this one firsthand. My communication firm hired the wrong agency to rebuild our website. It cost us $300,000, and the results were disastrous: Inbound traffic collapsed, and leads slowed to a crawl. Our business stagnated. The experience goes on record as our worst crisis ever.

Leadership had to step up to own this disaster. We communicated often, sharing evidence of what we were doing to fix it. We restructured our marketing team, which was a painful step. We reported openly at all-hands meetings about the recovery and how employees could help. Because we shared progress often, the employees could see where we were as we slowly recovered our revenue. You know what? It took almost two years, but we fixed it!

People do not expect perfection from their leaders, but they do expect leaders to explain what went wrong in plain language, name who is on point to fix it, and show the first milestones that will mark a way out of the woods.

The ‘Bounce Back’ Message

External shocks, such as fluctuating tariffs, supply breakdowns, and sudden regulatory changes, demand steadiness. The leadership voice should be calm, specific, and supportive. People want to know how the company will adapt operations, what flexibility they will have, and how success will be measured while conditions remain volatile.

When the COVID-19 pandemic froze travel, Airbnb CEO Brian Chesky’s transparent and empathetic communication about employee layoffs helped it navigate a crisis. In “the hardest email I’ve ever had to write,” he provided a clear, logical explanation for why the company needed to cut 25% of its workforce. He expressed appreciation for the departing employees, detailed their severance benefits, and rallied the rest of the team around a new, refocused mission. The transparency and clear path forward enabled the company to successfully launch its Online Experiences program, recover, and execute a long-in-the-planning, highly successful IPO just months later.

The ‘Shut It Down’ Message

Sometimes the right decision is an ending. That requires honoring the work, unearthing the learning, and spelling out where people, budgets, and valuable assets will go next. Closure prevents zombie projects from consuming attention and allows talent to reattach to meaningful work.

Closure prevents zombie projects from consuming attention and allows talent to reattach to meaningful work.

Startups are especially prone to this kind of moment. For instance, in early 2024, it was announced that Artifact, an AI-powered news app built by Instagram cofounders Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger, would be shutting down, a year after launch. Systrom explained the decision in a Medium post, saying that though the app had a loyal user base, the market opportunity wasn’t large enough for the owners to justify ongoing investment. “The biggest opportunity cost is time working on newer, bigger, and better things that have the ability to reach many millions of people,” he wrote. He praised the team’s achievements while framing the closure as a strategic necessity, which gave the venture a respectful ending. (As it turns out, that wasn’t the end of the idea: Yahoo bought Artifact a few months later, saying in a press release that “the technology Artifact has created will be even more impactful with the scale of the Yahoo News network.”)

The ‘Move On’ Message

When the world changes in ways that make the usual path untenable, the leadership job is to help people release the past and attach hope to the future. Endings in this circumstance require more than a memo; they benefit from symbols and ceremonies that put the changes in a broader context and make the transition feel real.

A vivid example is the theatrics by Apple cofounder and then-CEO Steve Jobs at the company’s 2002 Worldwide Developers Conference. To end the era of the original “classic” Mac OS operating system, Jobs staged a mock funeral. Organ music played. A coffin sat on stage. Jobs delivered a brief eulogy declaring OS 9 “dead.” It was dramatic and playful, but the message was unmistakable: Stop building for the old world and move your energy to Mac OS X. He honored what had been built, made the ending memorable, and redirected the developer community’s attention to the future.

Regardless of whether leaders must fix or finish, and regardless of which of the four message types they deliver, there are basics that should be included in every message. Employees and team members need to hear empathy, appreciation, disclosure, and some element of persuasion.

When a client lost most of their project work almost overnight, we helped them develop a script for their communication. Bad news lands as loss, and leaders first empathized with staff members, naming the human difficulty. Leaders spoke of how much they appreciated everyone’s work. They disclosed mistakes, stating the truth plainly. Leaders then shifted to persuade mode, rallying employees. (“There’s a future worth building, and we’ll build it together.”)

Delivering bad news is not about finding the perfect words to soften a blow. It is about telling the truth in a way that preserves trust and mobilizes people for what comes next. Name the moment you are in — fix it, bounce back, shut it down, or move on — then speak with empathy, appreciation, disclosure, and persuasion.

Bad news may end a chapter, but it can also concentrate energy. Leaders who master how to say the hard thing, at the right time, with the right words, free their organizations to do the next big thing.