How to Foster Talent Management Champions

Many managers pay insufficient attention to talent strategy. Five interventions can help deepen their commitment to identifying and developing key capabilities.

News

- Adani Power Sets Up Nuclear Subsidiary

- Musk Unveils xAI Overhaul, Lunar AI Ambitions

- Former GitHub CEO Dohmke Raises $60 Million to Build AI Code Infrastructure

- Leadership Shakeup Deepens at xAI as Two Co Founders Exit

- India Slashes Social Media Takedown Window to Three Hours

- Cisco Moves to Relieve AI Data Center Gridlock With New Chip

As leaders juggle increasingly complex and demanding responsibilities, they can substantially differ in their commitment and approach to managing talent. While some leaders proactively identify, develop, retain, and deploy talent, others neglect these activities. That can be detrimental for organizations amid ongoing skills shortages and rising employee expectations for career development, continuous learning, and recognition.

A strategic organizational talent management approach, bolstered by leader buy-in, is a powerful mechanism to develop greater operational agility by enabling more fluid and flexible workforces. Deliberate approaches and tools can facilitate talent mobility and enhance strategic deployment by dynamically matching employees’ skills with organizational needs.1 For example, research has found that internal talent markets can increase employee engagement and reduce turnover, but their effectiveness depends on collaboration beyond functional silos — a deep cultural shift for many organizations.2 Leadership commitment to managing talent is paramount.

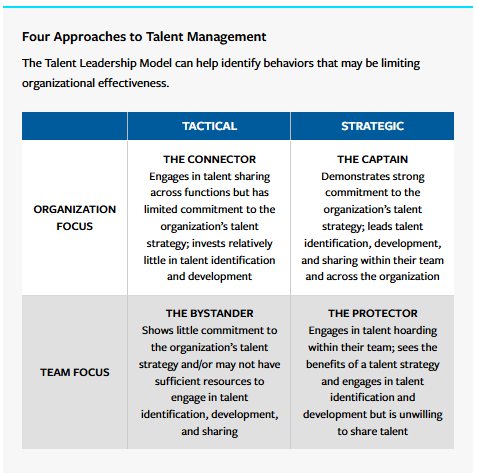

Here, we will introduce the Talent Leadership Model, developed through our interviews with middle managers, which describes the varying roles and behaviors that leaders exhibit when managing talent. (See “Four Approaches to Talent Management.”) Senior executives can use this framework to better understand the talent leadership styles of their organization’s team leaders, as well as their own approaches, in order to help managers become more effective contributors to an enterprisewide talent strategy.

Four Talent Management Approaches

Our model describes four different talent management approaches along two key dimensions: leaders’ strategic depth (tactical or strategic) and scope of impact (across their own team or the whole organization).

1. The Bystander. These managers take a detached approach to managing talent, demonstrating little engagement in talent identification and development, or showing minimal commitment to the organization’s talent strategy. Bystanders often focus on short-term, operational needs, neglecting more long-term, strategic considerations, such as the development of a talent pipeline. Tending to focus on their own teams, bystanders make few efforts to engage in broader talent conversations.

In our research, we found three main reasons some managers have this attitude. Most commonly, these managers felt the need to focus on activities core to their own performance evaluations. This indicates that if talent management is not a factor in a manager’s evaluation, it can easily become a low priority for them. In addition, some managers reported having insufficient resources, training, or knowledge to properly manage talent. Finally, some managers simply couldn’t be bothered — they had no commitment to the organization’s talent strategy and considered talent management an unimportant matter that should be delegated to HR.

Bystanders’ limited involvement in talent development can cause employee disengagement and subsequent attrition. Their noncommittal approach to talent management can substantially weaken the leadership pipeline and lead to detrimental succession planning decisions.

2. The Protector. Protectors hoard talent. They understand the value of identifying and developing talent and have a long-term perspective. However, their focus is limited to their own team, and they try to keep talent under their control.

Leaders who adopted a protector role cited a variety of reasons for their approach. Many managers highlighted the need for team stability and considered talent mobility “counterproductive” and disruptive. If a manager relied on talented staff members to deliver result and those individuals moved to other opportunities within the organization, their mobility could negatively impact the team’s — and the manager’s — performance. Some managers who expended time and resources on employees’ growth and development expressed concern that they would lose returns on their investment if a team member subsequently moved to another department. A few managers resisted talent mobility due to a lack of clarity around how to replace employees lost to new assignments.

Protectors tend to have a narrow perspective and fear losing talent to other functions rather than to other organizations. They can stall individuals’ careers, leading to employee dissatisfaction due to limited growth opportunities. Protectors’ defensive approach may mean that they withhold information useful for dynamic skills matching, limiting an organization’s ability to adapt to changing environments.

3. The Connector. These managers engage in a sharing approach, facilitating rotations and transfers across functions, but are not strongly committed to the organization’s talent strategy. Despite frequently operating across functional boundaries, these leaders engage little in value-adding talent identification and development and instead take a short-term, operational perspective. We found that some managers acted as accommodating connectors to avoid being seen as blockers.

Across organizations, connectors were open to talent rotations but did not want to be involved in the details of talent management, considering it HR’s domain. They saw little incentive to align their own practices with broader organizational talent strategies. This is problematic because talent investments made through rotational or transfer programs may not yield the hoped for results if talent is not thoroughly evaluated in terms of suitability for the rotation or transfer. Connectors therefore accept the risk of talent mismatch, subsequent underperformance, and inefficient talent development investments.

4. The Captain. These leaders are willing to take the wheel and steer talent management efforts. They take a long-term, strategic, organizationwide perspective. Captains are aware of and committed to the organizational talent strategy and understand the importance of talent identification, development, and retention. They enable talent sharing across organizational units.

In our research, captains stood out for their proactive approaches. They considered themselves stewards cultivating future leaders for the entire organization. Leaders who had this perspective considered the organization to be an internal talent market where talent mobility, development, and retention can be fostered in a way that enables both employees and the organization to win in the long run. Once individuals were identified as talents, they were strategically deployed within the internal market. For instance, one manager regularly met with counterparts in other departments to discuss talent needs and potential moves aligned with the strategic priorities of the organization.

Captains skillfully deploy talent, strengthening the organization’s agile business operations, and can be considered ambassadors for managing talent companywide. However, these leaders must carefully manage relationships with other stakeholders to avoid perceptions of talent poaching. They must also minimize employees’ and managers’ concerns about high levels of internal talent mobility, which can affect team stability and operational effectiveness if not managed carefully.

Cultivating Talent Management Commitment

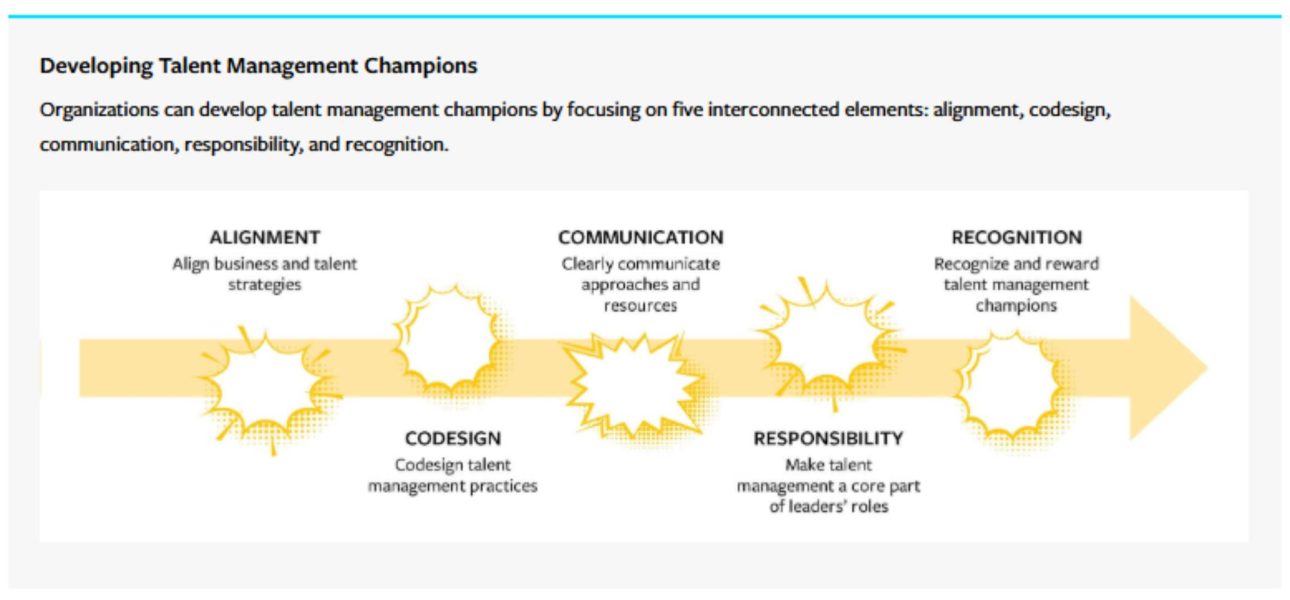

To build sustainable pipelines, organizations need more captains who champion talent management with a long-term, strategic perspective. We propose five ways to cultivate these team leaders. (See “Developing Talent Management Champions.”)

Align business and talent strategies. Alignment is needed to create a shared vision and implement strategies that will have a positive organizational impact. A first vital step is to clarify what core capabilities the organization needs to execute on its strategic priorities. For example, a Swiss pharmaceutical company identified critical current and future capabilities related to biopharma, data insights, and technology. Subsequently, it evaluated the need to either acquire them through skills-based hiring or develop them internally through leadership programs and targeted upskilling and reskilling initiatives.

Similarly, a Dutch electronics firm established capability alignment workshops where HR and business leaders discussed skill needs for future projects. This approach was also adopted by a German automobile manufacturer that established quarterly workshops to systematically map its strategic direction against current and future employee capabilities. Since the implementation of these workshops, the company has reported a 25% improvement in its ability to fill critical roles internally.

Aligning business and talent strategies clarifies expectations and shows leaders the value of talent management, positioning it not as a peripheral HR responsibility but a critical enabler of business goals for the entire company. Moving from a team-level focus to an organizationwide scope of impact and from a tactical perspective to a strategic one, talent management becomes part of leaders’ identity rather than a distraction. This shift requires convening managers to discuss talent management as a critical piece of strategy execution. This should take place as part of strategic planning cycles, workforce planning sessions, and leadership development programs. For example, a German consumer goods company relied on internal role models who shared their operational success and explained their alignment between business and talent strategies in a series of workshops. Using case studies and success stories can help other leaders understand the impact of talent practices on business performance and inspire them to become talent champions in the organization.

Codesign talent management practices. Organizations can get greater buy-in from mid-level leaders by codesigning talent management initiatives. This helps establish talent management as a shared responsibility.3 Leaders see how practices fit their context, making them more likely to try, adapt, and sustain new behaviors.

In our research, a U.S. automobile manufacturer empowered leaders with specific responsibilities. Leading a talent task force, for example, gave them an opportunity to have a hands-on role in shaping consistent, organizationwide talent practices, which in turn built their confidence and competence around managing talent. The task force helped establish shared definitions, development frameworks, and advancement pathways, creating a more transparent, fair, and cohesive employee experience across departments. The initiative also shifted leaders’ perspectives from a siloed team focus toward organizationwide thinking.

Similarly, a U.K. consumer goods company ran regular cross-departmental meetings to brainstorm central talent challenges and potential solutions, and a Dutch bank launched talent management innovation labs where leaders could propose and pilot talent management initiatives. Successful proposals were funded for organizationwide implementation. This initiative resulted in greater levels of adoption by business leaders, who championed talent management for the organization.

Clearly communicate approaches and resources. Organizations must provide clarity on their talent philosophy, priorities, and practices and the available resources for talent management. Finding ways to communicate talent strategies succinctly but holistically to business leaders allows for greater consistency in decision-making and more effective implementation. Organizations can use digital platforms, governance structures, and communities of practice to improve communication.4 Ultimately, this facilitates leaders’ internalization of the purpose of talent management and helps build shared understanding.

For example, a U.K. consulting group invested in a talent navigator platform, providing managers with access to real-time insights and supportive resources, including key talent analytics, development support, and succession planning tools. The platform increased transparency and engagement with talent strategies and practices and led to more internal promotions. The U.K consumer goods company noted above established a talent strategy council encompassing talent champions and C-suite members, who met on a quarterly basis to disseminate and debate talent strategies.

Finding ways to communicate talent strategies succinctly but holistically to business leaders allows for greater consistency in decision-making and more effective implementation.

Some organizations have established more frequent mechanisms to communicate talent strategies and practices. For instance, a Swiss pharmaceutical company established 30-minute biweekly talent strategy sessions. The touchpoints allowed HR teams to share updates, market trends, and success stories. Since introducing the sessions, the company has reported a 35% increase in talent mobility across functions. A similar approach was adopted by a Swedish retailer, which introduced biweekly cross-functional meetings to exchange knowledge that led to innovative talent engagement practices. Focusing more on network-building, the U.K. consumer goods company created an internal talent management champions network — a community of practice to regularly share best practices and provide support.

Clear communication gives leaders the tools and context to act strategically rather than tactical and creates a mindset where talent is seen as a companywide asset.

Make talent management a core part of leaders’ roles. Talent management efforts are imperative to any leader’s role, not one-off exercises or tick-the-box compliance requirements. Managers must continuously engage in identifying high performers and high-potential employees and supporting their development, performance, and deployment — a responsibility that should be factored into the design of leadership roles.

One U.S. investment bank requested that operational leaders regularly participate in talent review meetings to proactively identify high-potential employees and successors within their organizational units. Both German and U.S. automobile manufacturers established contractlike talent agreements that clarified individual leaders’ talent development responsibilities within their function. These agreements, made collaboratively across business units, also stipulated agreed-upon procedures for talent rotation.

To manage leaders’ cognitive loads, talent management responsibilities should be embedded in their existing, core responsibilities rather than treated as additional tasks. Instead of writing generic job description statements such as “managing teams,” organizations can specify the need to identify high potentials and/or successors; to develop talent through training, coaching, and mentoring; and to deploy those employees in internal markets. Consequently, leaders will adjust their daily behavior, reflecting the explicit expectation that talent management is a core part of their role. Leaders become more intentional about talent management by dedicating time to it, prioritizing team development, and embedding talent-related decisions into their everyday actions.

Talent management efforts are imperative to any leader’s role, not one-off exercises or tick-the-box compliance requirements.

Recognize and reward talent management champions. Holding all leaders accountable for identifying, developing, retaining, and deploying talent requires a clear set of goals and metrics that can be measured regularly. Beyond operational KPIs, this may include talent retention rates, engagement scores, succession planning efforts, internal mobility, and learning and development activities.

Recognizing and rewarding talent management champions shifts leaders’ behaviors from optional talent management practices to proactive investment and in turn into talent identification, development, and retention. Tangible or social recognition touches on extrinsic and intrinsic motivators, making leaders more likely to engage in strategic, organizationwide talent management. Through these clear incentives, talent management becomes a priority rather than a discretionary or mandatory effort.

For example, the U.K. consumer goods company ensured visibility and accountability by establishing a talent dashboard with clear KPIs that were reviewed on a quarterly basis, and managers were asked to present their talent management activities, successes, and challenges to senior leadership quarterly as well. Similarly, a U.S. consumer goods firm assessed each organizational unit based on its ability to identify, develop, engage, retain, and deploy talent.

The German consumer goods company mentioned previously went further, aligning its performance evaluations and reward structures with talent management engagement. Manager bonuses were tied to proactively sharing and strategically deploying talent across functions. After implementing such an arrangement, organizations need to be cautious that this engagement remains genuine and is not just driven by incentives.