What Jane Goodall’s Career Teaches Us About Allyship and Sponsorship

Just as Louis Leakey advocated for Jane Goodall and other women scientists, today’s leaders can create lasting impact through authentic sponsorship and inclusion.

News

- Adani Power Sets Up Nuclear Subsidiary

- Musk Unveils xAI Overhaul, Lunar AI Ambitions

- Former GitHub CEO Dohmke Raises $60 Million to Build AI Code Infrastructure

- Leadership Shakeup Deepens at xAI as Two Co Founders Exit

- India Slashes Social Media Takedown Window to Three Hours

- Cisco Moves to Relieve AI Data Center Gridlock With New Chip

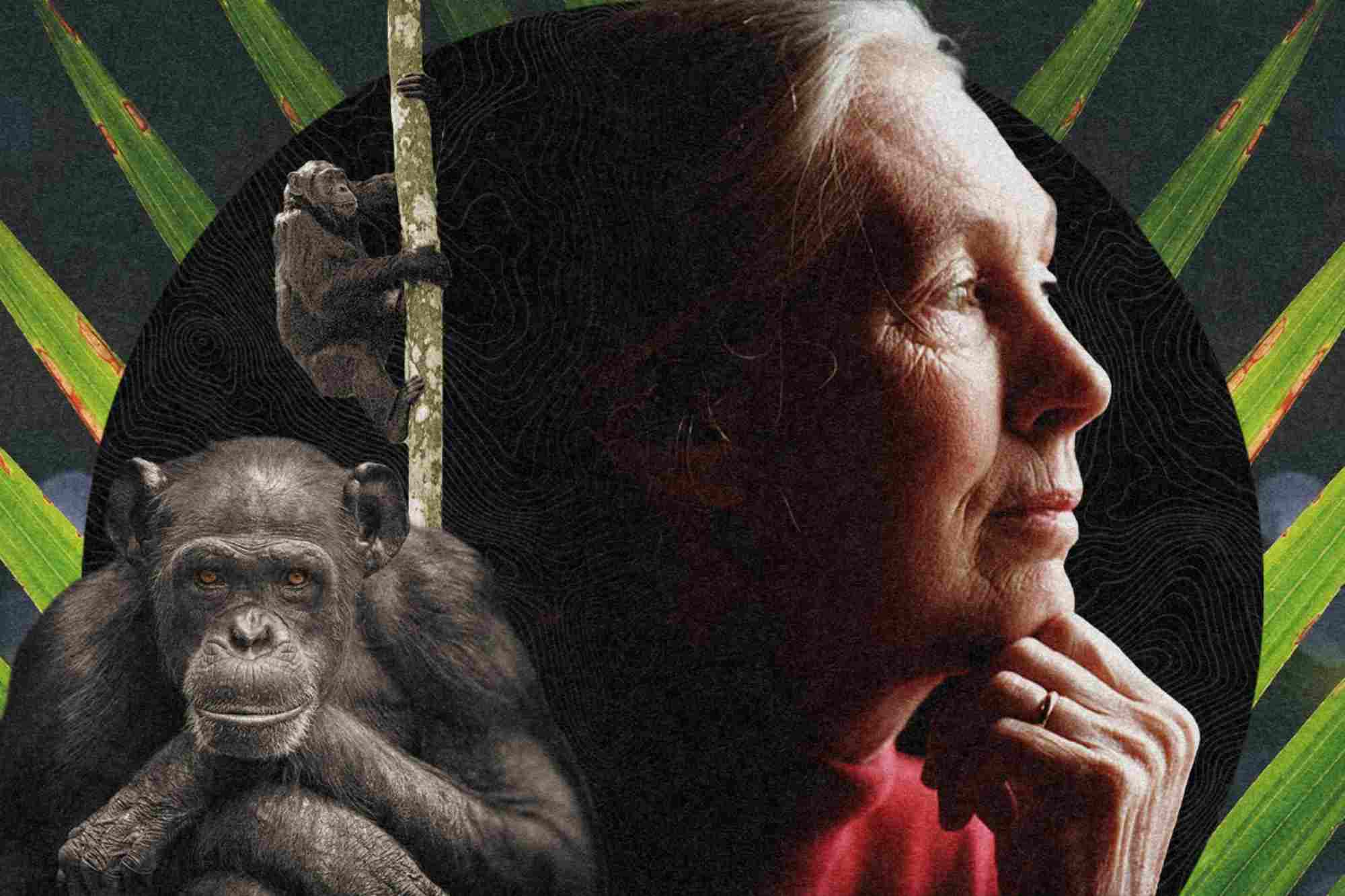

Carolyn Geason-Beissel/MIT SMR | Colin McPherson/Corbis Premium historical via Getty Images

When Jane Goodall died in October, the world lost more than a scientist. It lost a moral compass: a woman whose quiet persistence taught humanity to see connection where it once saw hierarchy. Her decades of observing chimpanzees in Tanzania reframed our understanding of intelligence, empathy, and cooperation. Yet Goodall’s story is also one of leadership — of what happens when someone in power sees potential in those the system has overlooked.

Long before Goodall became a household name, British-Kenyan paleoanthropologist Louis Leakey recognized her patience, intuition, and curiosity. Lacking formal credentials, Goodall was working as a secretary when the two met. Leakey used his credibility to sponsor her research on chimpanzees, secure funding, and legitimize her in a male-dominated field. He later supported Dian Fossey (studying mountain gorillas) and Biruté Galdikas (studying orangutans) as well. The three female scientists, collectively dubbed the “Trimates,” would each go on to transform the study of primates and reshape public understanding of life on Earth.

Leakey and Goodall’s relationship offers today’s executives something rare: a time-tested model of allyship and sponsorship that works. At a moment when many organizations are retreating from diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) efforts, Leakey’s behavior illustrates how authentic sponsorship and inclusion can generate long-term effects.

Cultivating Talent: Five Lessons

1. Use Your Power to Open Doors

Leakey wielded his institutional reputation to advocate for women scientists, long excluded from field research. He publicly endorsed Goodall (and other women), leveraged relationships with funders, and attached his own name to his mentees’ work — lending credibility they otherwise would have been denied.

This exemplifies what researchers M.A. Warren and M.T. Warren have called virtue-based allyship — the deliberate use of moral courage, prudence, and compassion to act on one’s values, even when it carries risk.1 Modern leaders can mirror this behavior by sponsoring underrepresented employees for visible assignments, naming their contributions in executive forums, and taking personal responsibility for creating opportunity.

As David G. Smith and W. Brad Johnson argue in their book Good Guys, allyship from those with positional power is most effective when it redistributes opportunity, not just empathy.2

Leakey’s choice to stake his reputation on others’ promise captures this principle.

2. Value Competence Over Credentials

Leakey’s support for Goodall (then an untrained researcher) defied the credentialism of his era. He prized her observational acuity, patience, and empathy over degrees or pedigree. He later applied the same principle with Fossey and Galdikas, focusing on potential rather than credentials.

Research shows that highlighting others’ strengths in moments of bias improves both inclusion and well-being.3 Rather than simply denouncing discrimination, effective allies redirect others’ attention toward marginalized employees’ capabilities, reframing competence narratives.

Leaders can follow suit by broadening talent criteria beyond formal credentials, recognizing emotional and relational intelligence as vital assets, and investing in potential others may undervalue. Inclusion, in this view, is not about lowering standards: It is about expanding vision.

3. Empower Through Trust and Autonomy

Leakey’s allyship extended beyond access. He gave his protégées genuine autonomy: the freedom to define research questions, design research methods, and publish independently. At a time when most women scientists were relegated to assistant roles, this level of trust was revolutionary.

Empowerment is also central to organizational allyship. My co-researchers and I found that inclusive leaders cultivate safety by modeling humility, curiosity, and vulnerability rather than projecting perfection.4 Likewise, other research indicates that allies pairing advocacy with celebrating their colleagues’ strengths, talents, and achievements is highly effective in fostering a sense of inclusion and well-being among marginalized group members.5

Executives can emulate Leakey’s stance by delegating meaningful authority, providing resources rather than control, and celebrating initiative even when results are uncertain. Empowerment transforms allyship from momentary intervention into enduring confidence.

4. Pair Allyship With Shared Purpose

Leakey’s motivation was not charity; it was mission. His goal — to understand humanity’s origins — demanded diverse perspectives. Supporting women was, to Leakey, strategic: Expanding inquiry required expanding participation.

Research shows that when organizations integrate allyship and inclusion into their core purpose, they outperform those that relegate diversity and inclusion efforts to side programs.6

Another study, on values-based allyship development, found that allies succeed when their actions align with organizational goals and moral identity.7 Similarly, studies have demonstrated that inclusive leadership enhances team creativity and retention precisely because it connects fairness to performance.

Supporting women was, to Louis Leakey, strategic: Expanding inquiry required expanding participation.

5. Practice Allyship Across Multiple Areas

Beyond his professional mentorship, Leakey practiced allyship in his personal life, most visibly through his partnership with his wife, Mary Leakey, a pioneering archaeologist whose discoveries in Tanzania advanced evolutionary science. He credited her precision and discipline as equal to his own, modeling respect that transcended convention. He also supported the intellectual paths of Meave Leakey (his daughter-in-law), a renowned paleoanthropologist researcher at the National Museums of Kenya; and his granddaughter, Louise Leakey, a paleoanthropologist and science communicator whose career was profoundly shaped by the legacy and infrastructure her grandfather had built — the Leakey Foundation, museum networks, and research camps he founded.

Goodall once said, “What you do makes a difference, and you have to decide what kind of difference you want to make.”

The work of Smith and Johnson demonstrates that authentic allyship requires congruence between personal values and public behavior. When leaders act inclusively both inside and outside of work, employees perceive their allyship as genuine rather than performative.9 Conversely, inconsistency erodes credibility.

Modern leaders can strengthen their credibility by modeling equality at home, sharing caregiving or mentoring roles, and ensuring that their leadership persona reflects their private ethics. As Louis and Mary Leakey’s partnership illustrates, allyship is not a professional tactic but a personal practice.

The Ripple Effect

Louis Leakey’s allyship and sponsorship generated a ripple of impact that outlived him. Goodall, Fossey, Galdikas, and Mary Leakey each mentored new generations of scientists and advocates, transforming public consciousness around empathy and conservation. Their success shows that empowering someone can reshape entire systems.

The same dynamic applies in organizations. Research has shown that although inclusive leadership is challenging and can cause stress and frustration for leaders, it is ultimately beneficial.10 Acting as a moral contagion, inclusive leadership spreads trust, safety, and collaboration across teams, and positively affects customers and other external stakeholders.11 Similarly, Smith and Johnson showed that visible allyship cascades in an organization: When leaders model inclusion, peers and subordinates emulate the behavior, creating cultural momentum.12

References

1. M.A. Warren and M.T. Warren, “The EThIC Model of Virtue-Based Allyship Development: A New Approach to Equity and Inclusion in Organizations,” Journal of Business Ethics 182, no. 3 (January 2023): 783-803, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-05002-z.

2. D.G. Smith and W.B. Johnson, “Good Guys: How Men Can Be Better Allies for Women in the Workplace” (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Press, 2020).

3. M.A. Warren, “Amid DEI Rollbacks, Champion Allyship,” MIT Sloan Management Review, March 5, 2025, https://sloanreview.mit.edu.

4.W. Zheng, J. Kim, R. Kark, et al., “What Makes an Inclusive Leader?” Harvard Business Review, Sept. 27, 2023, https://hbr.org.

5. M.A. Warren, T. Sekhon, and R.J. Waldrop, “Highlighting Strengths in Response to Discrimination: Developing and Testing an Allyship Positive Psychology Intervention,” International Journal of Wellbeing 12, no. 1 (2022): 21-41, https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v12i1.1751.

6. Q.M. Roberson, “How Integrating DEI Into Strategy Lifts Performance,” MIT Sloan Management Review, Nov. 7, 2024, https://sloanreview.mit.edu.

7. Warren and Warren, “The EThIC Model,” 783-803.

8. Roberson, “How Integrating DEI Into Strategy Lifts Performance”; and Smith and Johnson, “Good Guys.”

9. Smith and Johnson, “Good Guys.”

10. W. Zheng, J.Y. Kim, and R. Kark, “Every Rose Has Its Thorns: How Exemplars Manage the Tensions in Inclusive Leadership,” Journal of Business Ethics, April 30, 2025: 1-21, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-025-05993-z.

11. Zheng et al., “What Makes an Inclusive Leader?”

12. Smith and Johnson, “Good Guys.”