AI in Policing: India’s Test Case for Rights, Accountability, and Public Trust

As AI increasingly enters policing, India faces the challenge of using powerful tools without compromising rights or accountability.

Topics

News

- How AI Chatbots Pose Risks When used for Medical Advice

- Anthropic Safeguards Lead Sharma Steps Down Over Values and Risk

- Meta, Google Face Landmark Trial Over Addictive Social Media Design

- Hackers Breach Government Systems Worldwide

- Cyber Risk Rises to the Top of India Inc Worry List

- India, Malaysia Bet on Semiconductors to Deepen Ties

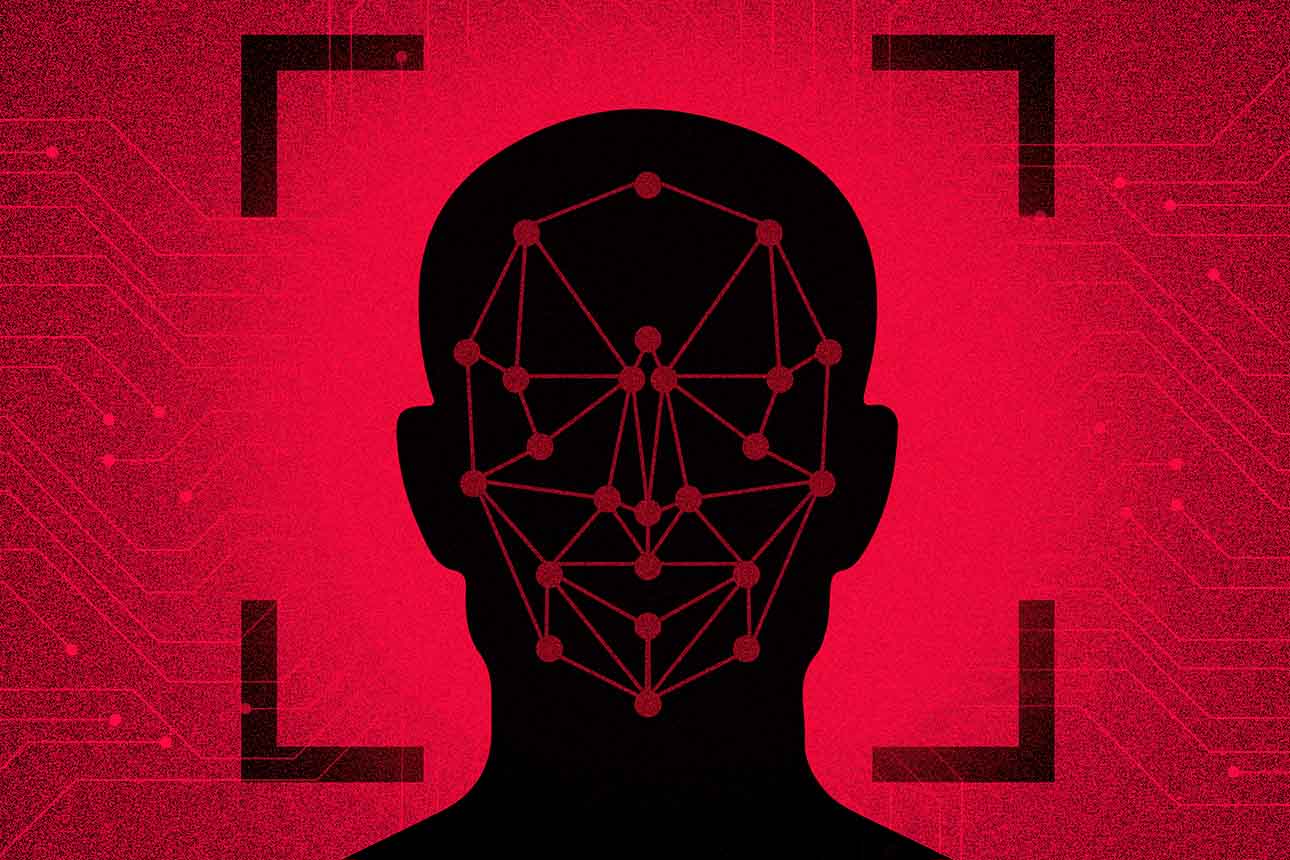

The role of artificial intelligence in Indian policing is expanding, a shift that has intensified debate over how law enforcement can use advanced tools while staying within legal and constitutional limits.

One investigation in Delhi last year shows how fast the change is unfolding. Officers struggled to identify a murder victim whose face had been mutilated beyond recognition. They turned to an AI model to reconstruct the man’s features and produce a usable image that could be circulated publicly. The police uploaded it to the national Crime and Criminal Tracking Network (CCTNS), eventually locating the victim’s family and arresting four suspects.

Within the police force, the case is now cited as an example of how new technology can revive leads that would once have collapsed for lack of information.

In Kerala, technology helped close a triple murder from 2006 that had remained unsolved for nearly two decades. Police used an AI system to create age progressed versions of two suspects who had vanished after the killings. Investigators then searched for matches online, including on social media platforms.

One of the enhanced images aligned with a wedding photograph circulating on social media. Officers tracked the suspect to Puducherry and arrested him in January. His associate was found soon after.

These breakthroughs have encouraged senior policing officers to call for broader adoption. At a national security conference in Delhi this year, Union Home Minister Amit Shah urged police officers to use artificial intelligence and modern forensic tools to “deliver justice more efficiently,” while protecting constitutional rights.

The message reflects a national effort to modernize policing at a time when India is rewriting its criminal laws and expanding digital infrastructure.

Technology lawyers said the Delhi and Kerala cases show what AI can achieve when used carefully.

Advocate Ankit Sahni, intellectual property and technology law expert, said the investigations “illustrate how AI-enabled facial technologies, when confined to narrow and proportionate investigative contexts, can meaningfully support policing.”

He said this is where technology “legitimately augments, rather than displaces, police judgment.”

Others argued that the same tools raise significant legal obligations that police forces are not yet equipped to meet.

Advocate Sameer Avasarala, Technology, Media and Telecommunications (TMT) lawyer and Principal Associate at a legal firm Lakshmikumaran and Sridharan said AI is now present “in all aspects of law enforcement, from prevention to prosecution,” and that it is essential to “contextualize, assess, and identify emergent risks” related to privacy, algorithmic bias, explainability, and the need for human oversight.

He pointed to the Supreme Court’s privacy ruling, which requires reasonability and proportionality whenever the State intrudes into personal data.

He said the Digital Personal Data Protection Act reinforces the need for “reasonable security safeguards,” and that meeting proportionality standards is critical for balancing investigative needs with civil liberties.

The legal framework around AI-generated material is also incomplete. India’s new evidence law recognizes digital records, but Sahni said AI-generated or AI-enhanced images “remain illustrative or demonstrative aids.”

Courts, Sahni noted, will need “proper authentication, demonstrable accuracy rates, reproducibility, metadata integrity, and expert testimony” before giving such material weight.

Kartikeya Raman, an Associate Partner at Grant Thornton Bharat said Indian courts remain cautious about such material. “AI-generated facial recognition is treated as corroborative, not conclusive proof,” he said, adding that judges “insist on expert testimony to explain the model’s process, accuracy and limitations before considering it reliable.”

Sahni, meanwhile, warned that treating AI outputs as final proof “would risk significant procedural unfairness.”

Raman said courts also examine error rates, chain of custody and data integrity before admitting AI-generated material, adding that judges “rarely accept it without human validation or corroborating evidence.”

India’s broader criminal laws have also not caught up with the technology. Sahni said the recent legislation does not clearly address “algorithmic processing,” “biometric inference,” or “probabilistic image-based identification.”

He pointed to the Criminal Procedure (Identification) Act of 2022, which expands the State’s authority to collect biometric and physical measurements but does not provide detailed safeguards for techniques such as facial reconstruction, age progression, or cross-database matching.

He said this creates “a statutory gap between traditional forensic methods and contemporary AI-powered algorithms,” and highlighted “the urgent need for legal reforms.”

Raman said India lacks a dedicated law regulating police use of facial recognition. “There are no standalone statutes for AI-based identification by law enforcement,” he said, while noting that agencies instead depend on broader laws such as the IT Act and the DPDP Act, which “do not offer clear rules on transparency or algorithmic accountability.”

Ethical concerns run in parallel with legal ones.

“AI facial recognition systems often misidentify people from marginalized groups such as women and people of color,” Sahni said.

Raman said the same risks make facial recognition legally fragile when agencies rely on opaque systems.

“Many law enforcement agencies use proprietary algorithms without clear policies or independent audits,” he said, warning that the technology “enables mass, real time surveillance and disproportionately misidentifies women and people of color.”

Avasarala said the issue is not whether police should use AI but how they do so.

India needs “a clear and comprehensive framework” that aligns investigative use of technology with constitutional requirements, he said, adding that risks “beyond privacy, such as lack of explainability of output, potential bias and discrimination, and absence of clear accountability standards” must be addressed, especially if decisions rely on AI without human oversight.

Raman said India will need stronger procedural checks as AI becomes routine in investigations. “The question is not whether police use AI but whether safeguards match constitutional standards,” he said, noting that global frameworks, including the EU’s AI Act and several US state laws, “mandate far more transparency, auditability and rights of contest than India currently provides.”

The two murder cases offer an early look at the possibilities and tensions that come with AI-driven policing. The technology can revive dead ends, put investigations on the fast track, and help identify suspects who might otherwise remain anonymous. The more complex question is whether legal institutions can set boundaries that protect rights and maintain public trust as these tools move from isolated experiments to everyday practice.