The Forces That Shape AI’s Uneven Progress

Automation advances unevenly across tasks and roles. Understanding the friction factors that slow adoption can help leaders navigate workforce transformation strategically.

Topics

News

- Adani Power Sets Up Nuclear Subsidiary

- Musk Unveils xAI Overhaul, Lunar AI Ambitions

- Former GitHub CEO Dohmke Raises $60 Million to Build AI Code Infrastructure

- Leadership Shakeup Deepens at xAI as Two Co Founders Exit

- India Slashes Social Media Takedown Window to Three Hours

- Cisco Moves to Relieve AI Data Center Gridlock With New Chip

As artificial intelligence has begun to write code, pilot vehicles, and even diagnose disease, narratives of machines abruptly replacing humans have taken hold. However, the real story is slower, messier, and far more uneven. Across roles and industries, AI’s emergent capabilities form what’s often called a “jagged frontier,” where it excels at some tasks while struggling with others. As its capabilities progress, AI is racing to fully automate some tasks while slowing to a crawl or stalling entirely for others. Leaders who understand the factors that shape this nuanced reality will be able to guide strategy and talent with clarity and steady their organizations in the process.

A 2024 analysis of AI’s progress by McKinsey & Co. suggests that its unevenness shows up not just across jobs but within them, at the task level. The consultancy projects that by 2030, in its midpoint scenario, demand will fall steeply for some occupations, such as office support and customer service. This is because such roles center on tasks that AI can already handle, like entering data, processing invoices, taking orders, and responding to routine customer inquiries. However, demand will rise sharply for health professionals and other STEM-related professionals whose work centers on tasks that AI struggles to replicate, such as clinical judgment, empathetic care, and complex, nonroutine problem-solving. The dividing line isn’t job title — it’s task makeup. But what is it about certain tasks or roles that make them more or less amenable to automation?

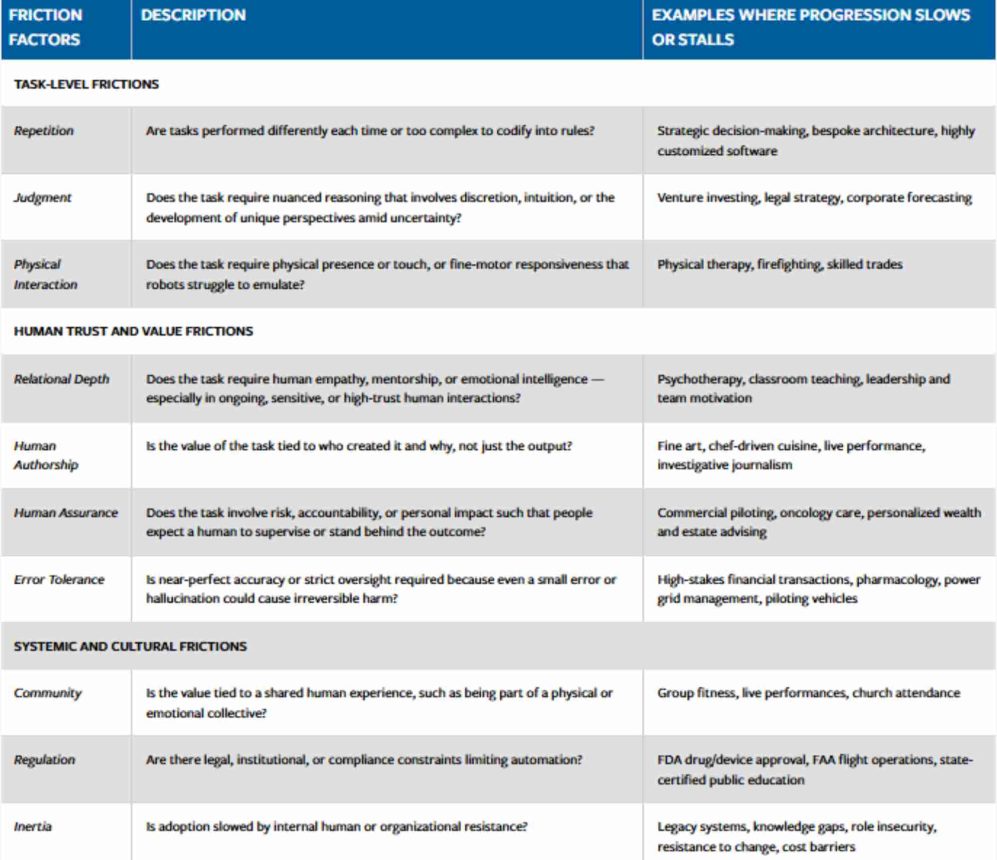

We’ve identified key friction factors — like repetition, regulation, judgment, and human assurance — that slow AI adoption. Based on those findings, we’ll offer a nuanced lens on why most jobs evolve in stages and at different speeds. The future of work won’t be defined by AI’s capabilities alone. It will also depend on the friction it meets.

What Slows AI From Quickly Taking Over Entire Roles?

Across industries, automation tends to follow an intuitive and familiar progression.

- Stage 1: Assist. AI handles repetitive, structured tasks that take up time but require little nuance.

- Stage 2: Reshape. Human responsibilities substantively shift toward interpretation, oversight, and higher-order thinking as machines take over core tasks and execution.

- Stage 3: Replace. Full automation occurs, with no human in the loop.

Rather than asking whether AI will entirely take over a job, a more constructive approach is to ask which tasks can be easily accomplished by AI tools and which are more resistant to automation. The table below offers a practical — though not exhaustive — look at why AI’s march is anything but uniform across the three stages. The friction points listed help to explain why automation races ahead in some domains but remains stubbornly human in others, and how leaders can better anticipate the next challenge on this uneven path.

Why Are Two Pilots Still in the Cockpit?

Pilots were among the earliest humans to share critical responsibilities with automation systems. Autopilot systems have been standard since the 1980s. Today, automation handles much of what pilots once did, such as navigating complex airspace and even performing fully automated landings in low-visibility conditions. However, though automation has assisted and reshaped pilots’ role, there are still two humans in the cockpit. The fact is, although pilots have evolved from manual operators to systems managers, their human presence remains essential. When we look to the factors described in “Friction Factors That Slow the Progress of AI,” it helps to explain why Stage 3 — replace — remains out of reach.

The barrier to full automation isn’t raw capability — it’s a stack of human, legal, and cultural constraints.

The need for human assurance remains high: Passengers still expect a human to be in the cockpit because lives are at stake. Judgment is essential: The role requires quick, unscripted decisions under uncertainty. Error tolerance is at or near zero, leaving no room for technical missteps. And regulation is slow-moving and cautious by design. The barrier isn’t raw capability — it’s a stack of human, legal, and cultural constraints. The European Union Aviation Safety Agency, for instance, anticipates that full autonomy for commercial aviation is unlikely to occur until sometime after 2050. In contrast, full autonomy is set to become viable much sooner for cargo and military aviation: Without passengers, there’s lighter regulation, less demand for human assurance, and a notch-higher error tolerance, and there are fewer high-stakes judgment calls to be made. That’s why drones, uncrewed freight, and fighter jets are moving faster through the stages. For this reason, entrepreneurs like Myles Goeller of Reliable Robotics emphasize starting with cargo and defense markets, where proving the safety of full automation can build the trust needed for its eventual adoption for passenger flights.

So while commercial passenger aviation may not reach Stage 3 for decades, other sectors within aviation will likely do so much sooner. This difference underscores the idea that even within the same broad profession, roles can occupy different stages and move at different speeds.

The same unevenly phased evolution is underway in medicine, education, finance, and most other domains. Understanding the friction points — both technical and human — is key to better managing what comes next.

Are Doctors, Coders, Teachers, and Self-Driving Cars on a Similar Flight Path?

Once you learn to spot the pattern, you’ll see it everywhere. Across industries, the same automation arc — assist, reshape, replace — emerges again and again. But the pace and outcome depend entirely on what the work truly demands.

Take medicine. In radiology, AI is deep into Stage 2. Tools like Med-PaLM — Google’s medical AI — perform on par with doctors in some diagnostic work, including reading scans and identifying anomalies. Yet front-line care tells a different story. Interpreting complex symptoms, weighing treatment paths, and communicating risk to patients still hinge on human assurance, inertia, judgment, and relational depth. Even within the field of medicine, AI’s progression varies, given that the underlying tasks and the factors influencing them have fundamental differences.

In software development, AI has moved fast. Tools like Copilot and Replit can scaffold apps and refactor boilerplate code. But moving from lower- to higher-stakes work — scoping ambiguity, debugging complex or regulated systems, architecting secure solutions, and working with evolving client needs — still depends heavily on error tolerance, human assurance, judgment, relational depth, and repetition. Stage 2 is well underway. But the pace toward full human replacement slows in more sophisticated areas where these factors dominate — something even AI leaders like Palantir reveal through its reliance on embedding its employees at client sites.

Friction Factors That Slow the Progress of AI

The future of work will be defined less by dramatic headlines and more by the slower reality of gradual, nuanced integration of AI.

Autonomous driving underscores how even when Stage 3 is technically demonstrated, it doesn’t guarantee full adoption. Waymo now operates fully driverless taxis in several cities — a clear example of Stage 3 achieved in a narrow domain. Yet, outside geofenced boundaries, autonomy remains partial, supervised, or nonexistent. Complex edge cases — such as construction zones and unpredictable human behavior — still require human oversight. And the internal costs and logistics of scaling production further limit the pace of full-scale deployment. As Uber’s CEO put it, full autonomy is still a decade or two away. Error tolerance, human assurance, inertia, judgment, and regulation continue to stall a broader rollout. And even then, progression will differ by city, state, and infrastructure.

Across these domains, the through line is clear: Automation isn’t always sweeping in to replace humans — it’s creeping in to reshape their responsibilities, one task at a time, at paces that vary across roles.

Final Descent: So, What Should You Actually Do?

The AI-driven future isn’t coming. It’s already here. The question now is how that future will unfold across different professions and industries. To lead effectively, executives should trade the panic over an overnight AI takeover for the more grounded reality of gradual AI integration.

AI is reshaping most careers — gradually, task by task and stage by stage. Factors like judgment, trust, regulation, community, error tolerance, and relational depth will either stall, slow, or accelerate the shift. That’s why roles like providing routine customer service and doing data entry are moving closer to Stage 3. Others, like teaching elementary school, conducting investigative journalism, and investing venture capital, have not and probably never will. These factors help to explain why some jobs will disappear quickly while others will remain deeply human for decades — if not forever. As The Economist has noted, even in vulnerable fields, broad job losses have been slow to materialize because AI is reshaping tasks more than it’s replacing workers.

This framework can help leaders anticipate where change is likely to happen fast — and where it may unfold more gradually. It can help guide decisions about where to invest, when to retrain, and how to evolve roles. It can also help leaders stay ahead of the curve without falling for hype or overreacting to headlines. In a moment filled with noise and alarm, one of the greatest strengths leaders can show is the ability to stay calm and grounded.